I just published an in-depth article in The Jerusalem Post Metro section, titled “Cracking the Technion’s Code,” about why the Technion was ranked sixth in the world in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology survey that evaluated entrepreneurship and innovation in higher education institutions. For anyone interested in understanding the start-up nature of Israel, this article provides a number of insights. Technion’s impact on the Israeli economy is pretty expansive: for example, two-thirds of the 72 Israeli companies listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange either were founded or are led by Technion graduates.

If you want to learn how Technion graduates have become so successful, you can see the full (non-pay-walled) article below. As always, I’d love your comments and suggestions.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Cracking the Technion’s code

With a degree for start-ups and a minor in entrepreneurship on offer, the university is in the business of encouraging innovations.

By LAURA ROSBROW

Photo by: LAURA ROSBROW

In an attempt to understand the impact of the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, the authors of the 2012 book Technion Nation: Technion’s Contribution to Israel and the World asked graduates of the institution a survey question that verged on the poetic: “Ernest Hemingway once wrote an entire story in only six words. It was ‘Baby shoes. Never used. For sale.’ Please describe your contribution to Israel and to humanity, in six words.”

Many responses touched on the diversity of Technion graduates’ technological accomplishments: “Provide poor countries with appropriate technology… Developed Intel’s 8087 microprocessor… Simulation software for unmanned drone aircraft.”

But one of the best and most straightforward answers was the following: “I came, I studied, I’m rich.”

The entrepreneurial spirit is so strong at the Technion that even MIT has noticed. In early April, the Technion ranked sixth in the world in a Massachusetts Institute of Technology survey that evaluated entrepreneurship and innovation in higher education institutions. The only universities that beat the Technion were MIT, Stanford, Cambridge, London’s Imperial College, and Oxford – meaning that the Technion scored higher than Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan, all of which have top-ranked business programs.

The Technion probably received this ranking in part because of its new partnership with New York’s Cornell University. In late 2011, New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg issued a first-time bid to universities around the world to launch an applied sciences graduate school in his city. The Technion partnered with Cornell, and both won the competition. Now Cornell Tech, which is in and of itself an innovation at the university level, will start offering limited programming this fall. The Roosevelt Island campus where Cornell Tech will be based is expected to launch fully in 2017, serving approximately 2,500 graduate students.

Aside from that partnership, though, the Technion’s numbers speak for themselves: Two-thirds of the 72 Israeli companies listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange either were founded or are led by Technion graduates; graduates of the institute lead nine out of the country’s 10 leading exporting companies; and one quarter of the Technion’s 67,000 alumni have at one time initiated a business.

Technion graduates largely drive the annual output of the country’s electronics and software industry, which is approximately $20 billion – half of the country’s total annual exports.

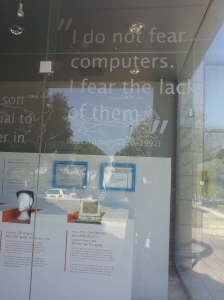

A glass window at the Faculty of Computer Science reads “I do not fear computers. I fear the lack of them.”

Long before Israel’s independence in 1948, graduates of the school – which was founded in 1912 – were helping to build the state. They developed much of the industry in the country’s early days, including roads, highways and desalination plants. More recently, they created technologies such as text messaging, drip irrigation, the disk on key, and the Arrow defense system. In the last eight years, three Technion faculty members have won Nobel Prizes.

While the Technion has greatly contributed to Israel’s becoming a “start-up nation,” the school is also a product of Israeli culture.

According to Prof. Miriam Erez, the associate dean of the Technion’s MBA programs and a recipient of the 2005 Israel Prize in management science, “entrepreneurial spirit is very Israeli. Israeli culture has all the ingredients necessary for entrepreneurship and innovation.”

Erez – an organizational psychologist – is the Israeli coinvestigator of the GLOBE Study of Leadership, an international group of social scientists and management scholars from 62 countries that studies cross-cultural leadership. Out of the values that the study compares, she says, Israel ranks well in those pertaining to entrepreneurship and innovation. Significantly, though, it has a moderate ranking in the most important value, collectivism versus individualism.

“The common research says that individualism enhances innovation, and collectivism discourages innovation,” she explains. “Israel is in between – not very individualistic, but also not very collectivistic. I think in today’s global culture, because entrepreneurship is to a large extent based on your network, if you’re a pure individualist, what is the likelihood that you’ll get support for your project, even if you have great ideas? I personally think this moderate level is best, which is exactly what we found here.”

This conclusion helps affirm why collective Israeli experiences, such as the army and university, foster local entrepreneurs’ networks.

Along with strong communities, the Israelis’ individualist side plays out in a value called “power distance,” in which Israel ranks very low. Erez explains that power distance is about hierarchy in society, such as the power distance between managers and employees. In cultures where that distance is higher, employees do not feel they can express their opinions.

That is not the case in Israel.

“People feel very comfortable criticizing their own bosses,” she says, noting that although it can be difficult to manage these kinds of employees, “this is exactly what you need for entrepreneurship and innovation.

[You need] people who feel free to express their own ideas and criticize until they find the best solution.”

Sitting in Erez’s office, one can tell that she nurtures her relationships. Near one of her large windows sits a 30-by-90-cm. paper tree, with the photos of several young people adorning the ends of each white branch. When asked about the tree, she smiles and says her students made it for her last year.

OVER THE years, she has maintained good contact not only with students, but also with industry professionals.

Her interest in creativity and innovation led her to found the Knowledge Center for Innovation, which aims to enhance innovation in Israeli industry.

One of those contacts was Uzi de Haan. Both were PhD students at the Technion at the same time. While Erez went into academia, de Haan went into industry, having been trained as an aeronautical engineer. In his last position, he was the CEO of Philips in Israel, which grew to $350 million in revenues under his management. When he retired from Philips at a relatively young age in 2003, Erez saw it as an opportunity and invited him to become a professor at the Technion. He accepted, wanting to teach entrepreneurship.

In 2004, he helped start the institute’s first entrepreneurship center. The Bronica Entrepreneurship Center, which began with only one course, now offers 17. In the fall, Technion students will be able to select an entrepreneurship minor.

The Technion also offers an international MBA program in English, with a similar program focused specifically on start-ups beginning this fall.

Alongside courses, the center offers assistance to early-stage entrepreneurs in developing business ideas, including to Technion alumni.

According to Keren Rubin, the center’s director, “in the last six years, the center has assisted in establishing more than 40 companies. We help them in the very early stage with the transition to the ecosystem.”

Although the center is of a modest size, with a handful of employee desks and a small conference table, it feels well-placed to grow. The office is located on the top floor of the Faculty of Industrial Engineering and Management. From one of its many windows, there is a bird’s-eye view of the modern, blue-and-beige-paneled Technion, and the industrial yet beautiful Haifa Bay at the bottom of the hill.

Asked why he thinks the Technion received the No. 6 ranking from MIT, de Haan answers, “We’re very much part of the ecosystem. Half of Intel’s engineers [in Israel] are Technion graduates. All those guys in tech companies are Technion graduates. We’re like a main supplier for engineers and innovation in Israel.”

It is no coincidence that Google, Yahoo, Apple, IBM and Intel have offices in Haifa.

They did this largely so they could recruit graduates from the Technion. Many students at the institute also work in industry while they study, applying what they learn in the field to their studies and vice versa.

Tal Goldman, an undergraduate student in computer science, works at the Technion’s Student Union.

He says he gains skills in this position that he would not gain in hi-tech – though he is sure his grade point average would be higher if he did not need to work.

In contrast, Tehila Sabag, an industrial engineering student who works for the Bronica Center, asserts that her studies “were not hurt because of my work. On the contrary, I think that because of my work experience, I am now a better industrial engineer and manager with more of a business perspective, rather than just an engineering one.”

She also values taking entrepreneurship courses, such as a popular one that Nobel Prize winner Dan Shechtman offers.

“The entrepreneurial activity that takes place here is the flagship of the Technion,” she says.

Goldman, too, sees such activity as a major part of the school’s efforts.

“I see the Technion’s investment in entrepreneurship all the time,” he says. “There are advertisements everywhere, such as in emails, posters, and from lecturers, to take part in entrepreneurial projects.”

THIS DEEP-ROOTED relationship between the Technion and industry is part of what makes the Bronica Center’s BizTEC competition so successful. Now in its eighth year, the student-run BizTEC is a national competition that selects the best student-led technology-based ventures. Winning the competition opens doors for many to connect with venture capitalists and interested funders from the center’s network of professionals.

Life Bond, one of BizTEC’s early winners, created biological sealants to seal bleeding tissue instantly. It has raised over $30 million.

More recently a start-up called Pixtr, which automatically corrects photos taken by mobile phones so that they look professional, accomplished several impressive early-stage goals thanks to the Bronica Center. In a select meeting between the center’s top start-up ventures and top industry mentors, a fairy-tale match was made: Uri Levine, the founder of Waze – which was voted Best Overall Mobile App in the Global Mobile Awards Competition in February – decided to become Pixtr’s mentor and chairman. He and the center helped Pixtr join Microsoft’s Azure Accelerator Program, which is aimed at early-stage start-ups. As part of the program, Microsoft provides office space, training, mentoring and other benefits.

“The most important thing about the center is the people,” says 30-year-old Pixtr cofounder Aviv Gadot, explaining what he feels has made the center a success.

“Uzi has so much experience and a great reputation within the industry, and Keren could move mountains. They are an amazing team.”

But for all the center’s success stories, there are many more start-ups that fail. Rubin asserts that the chances are “90% against you when you start.”

Still, asked if he thinks the start-up bubble has burst, as some leaders are saying, in light of the current budget deficit, de Haan quickly replies in the negative.

“Technology and economic growth are synonymous,” he says. “There’s an exponential growth in new technologies.

There’s no way big companies want to take on these new technologies. You need more and more start-ups to do this first innovation. Big companies don’t want to take the risk. They feel, ‘Why not outsource these crazy innovations to start-ups, and if they don’t fail, we’ll buy them.’” The problem, he notes, is how to fund those start-ups.

“But there are new mechanisms – crowd-sourcing, boutiques, venture capital, etc. There are ways to do it.”